Fernandina, Island of Iguanas

During the night, Lindblad’s National Geographic Endeavour crosses the equator to take us into the westernmost section of the Galapagos where the undersea upwelling creates cool water temperatures as low as the mid-50’s F. This cold water provides a rich marine smorgasbord for the sea lions, marine iguanas and flightless cormorants residing in the region.

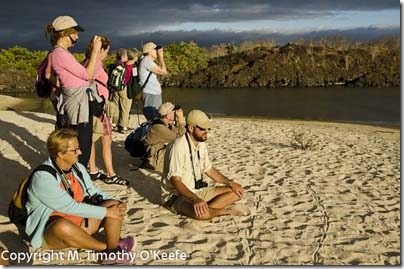

Our first landing of the day is on Fernandina Island, at one of the Galapagos’ best-known sites: Punta Espinosa, a narrow stretch of land and lava rock almost guaranteed to have a large concentration of animals, particularly marine iguanas. Darwin may have considered them hideous, but seen close-up, through a camera lens, their faces become captivating, almost appealing in a grotesque way; they certainly have character .

Fernandina Island, considered the youngest of all the Galapagos Islands, is still lively with volcanic activity. The last eruption here was in 2009, when the southern flank of the La Cumbre volcano had a fissure eruption that generated flows lasting for several hours. La Cumbre is considered among the Galapagos’ most active volcanoes, with eruptions in 2005 as well as 2009. Successive lava flows from the volcano have streaked the island in black, making this one of the most inhospitable islands for animal life living away from the shore. Because no animals were ever introduced, some consider Fernandina to be the largest, most pristine island remaining in the world.

This NASA satellite photo shows the volcanic plume from the 2009 eruption

This NASA satellite photo shows the volcanic plume from the 2009 eruption

of La Cumbre on Fernandina Island. The tiny section marked in red shows where unusually hot surface temperatures were detected.

From the Endeavour, Fernandina and its 5,000-foot volcano are an imposing sight. They become even more impressive as our Zodiac draws close, winding through a lava canal that leads to another over the bow scramble to stand on lava rock. This time I realize the Zodiac’s netting is not only to protect the rubber boat but also to provide us better traction when wave splashes slicken the bow.

Despite the thick lava crust bordering the shoreline, the National Park Service has managed to place posts in the rock to mark off a nature trail. We need the trail to guide us, too, because the dark lava rock is littered with black marine iguanas almost everywhere. When the animals are bunched up in groups of 20-50 animals, they’re easy to step around. It’s the stray animals (seeking solitude?) that demand careful attention while walking the path. Anyone who stops spotting to view what’s ahead–or where they intend to step next–is likely to find a marine iguana underfoot.

Our naturalist, Jeffo Marquez, says all these iguanas are males which are hanging together like best friends, partly to increase their body warmth. But when the mating season begins, he says all the buddy-buddy get-togethers abruptly end and it’s every male for itself as they compete for a female. Sounds like a familiar ritual.

We come upon a female sea lion reclining on the hard lava rock as her pup suckles. It’s a surprisingly noisy process that we can hear over the waves. Jeffo z points out how a sea lion mother will never nurse another pup, even one that’s been abandoned and starving. It’s already hard enough for a mother to find enough food to nourish her own, which she nurses from six to 12 months.

This is not puppy love. This is war.

Just as Jeffo ends sharing this tidbit of knowledge, two sleek and healthy sea lion pups, apparently drawn by all the nursing pup’s slurping sounds, suddenly appear from behind some rocks and quickly flipper-walk toward the nursing mother. She raises her head to issue a loud roar at them. That alerts her pup, which scrambles around to face the first aggressor. To protect his own feeding rights, the pup barks at the newcomer and aggressively nudges at it, attempting to drive away. The second interloper keeps its distance, seemingly unsure what to do. Finally the intruder sees this claim jumping isn’t going to succeed. It turns away and retreats, with its buddy close behind. The two come in our direction, realize we have nothing to offer, then plop down on the lava rocks. Excitement over.

“I love it when nature proves my point!” Jeffo exclaims.

Whale bones on display at Fernandina Island; lava cactus

Isabela Island Zodiac Ride

In the afternoon, we cross the Bolivar Channel to anchor near Punta Vincente Roca at the southern end of Isabela Island. A mid-afternoon Zodiac tour passing close to Isabela’s high rocky cliffs should show us the famous Galapagos penguins, flightless cormorants, sea turtles and the ubiquitous marine iguanas. However, the rough seas make this an unusually exciting outing and a challenging one for photography. That’s unfortunate because all the critters are present, including numerous sea turtles and several penguins that swim within yards of us. The motion of the bouncing boat is compounded by the deeply shaded area where most of the animals are hanging out; the angle of the sun would have been much better in the morning but the Endeavour has to follow the schedule given to it by the National Park. It’s disappointing to imagine the images that might have been.

Having an action-packed time in the waves off Isabela.

Later this afternoon, just before sunset, we’re scheduled to recross the equator. This time we’ll be able to celebrate the occasion, unlike last night when we slept through it. To mark the event, a bar with snacks is set up on the foredeck in front of the bridge.

Many of us assemble there or on the Endeavour’s bow to view Isabela’s amazing geologic formations. Isabela, at 62 miles (100 km) long, is the largest island in the Galapagos. It also is located near the “Galapagos hot spot,” an area where magma pushes through the ocean floor crust but quickly cools underwater to form a gentle sloping formation. As more magma is propelled from the hot spot, the slope keeps building until it reaches sea level and creates an island.

Isabela, considered among the youngest islands here at only one million years old, was formed by the merger of six “shield volcanoes,” so-named because of their large size and their low profile. Those two characteristics combine to resemble a classic warrior’s shield. The last eruption on Isabela took place in October, 2005; the eruption on Fernandina that same year was in May. An estimated 60 eruptions have occurred in the Galapagos over the past 200 years.

The cone of a shield volcano at Isabela Island.

As we continue to enjoy spectacular views of Isabela’s dramatic coastline, Endeavour expedition leader, Carlos Romero, announces all passengers should come on deck if they want to see the line when we cross the equator. Linda and I look at each other, wondering what is planned to create the famed but invisible equatorial line. We move to the ship’s upper deck for a better view.

Two naturalists, one wearing an Egyptian headdress, appear on the foredeck to unfurl a wide ribbon carrying yellow, red and blue stripes that match those of the Ecuadorian flag. Carlos starts a count-down to the moment the ship reaches the proper coordinates, then invites everyone “to cross the equatorial line.” People hesitate, wondering if the naturalists will decide to lower their equatorial line from shoulder level to knee level, which would demand some limbo action to squeeze under it. But the equatorial line stays stable at shoulder-height.

Crossing the line at the equator.

I decide to bolt from the upper deck to join in the line crossing. Linda follows but, being more petite and less pushy, falls behind. It’s a good thing one of us is at the equatorial line because Carlos is waving a single certificate marking this historic passage–and the certificate has Linda’s name on it.

Carlos calls me over to take her place. As he hands me the official-looking document signed by the ship’s captain, he tells everyone “And all of you will receive one!” His announcement prompts cheering and applause from all the passengers. Linda then shows up, just in time to take a photo of me holding her certificate.

This “ceremony” was unexpected and it was fun. But soon everyone’s attention moves to the horizon where the sun is about to set. And it’s going to be a pretty one.

Tonight, the Endeavour will almost circumnavigate Isabella to take us to locations many smaller ships don’t have the speed to reach for a normal seven-day Galapagos cruise. We’re especially looking forward to the first stop at Urbina Bay. We’ve been told about a section of coral reef that was moved almost a half-mile inland following a major upheaval in 1954. Just so something similar doesn’t happen tomorrow while we’re on land.

The moon rises over Isabela Island.

Lindblad Endeavour Galapagos Cruise Links

The Galapagos Experience Endeavour Dining

Galapagos Adventure Upcoming Sustainable Dining Policy

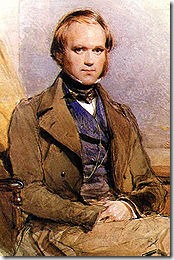

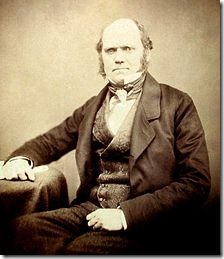

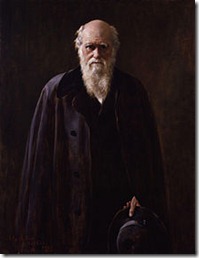

How Darwin Saved The Galapagos Saturday Dining Menus

Galapagos Photo Tips Sunday Dining Menus

What To Pack For Cruise Monday Dining Menus

Getting to Guayaquil Tuesday Dining Menus

Las Bachas Shore Landing Wednesday Dining Menus

North Seymour Shore Landing Thursday Dining Menus

Fernandina & Isabela Islands Friday Finale Menus

Urbina Bay Shore Landing Endeavour Recipes

Life Aboard The Endeavour

More About Life On Board

Puerto Egas Shore Landing

Endeavour’s Floating SPA

Meeting One of World’s Rarest Animals

Puerto Ayoro Walking Tour

Santa Cruz Highlands Tour

Hunting Tortoises in the Santa Cruz Highlands

San Cristobal, Endeavour’s final stop

Follow

Follow

Fill flash would remove the shadowing from this Galapagos hawk’s eye

Fill flash would remove the shadowing from this Galapagos hawk’s eye