Isabela Island from the Endeavour en route to Urbina Bay

Urbina Bay Hikes

The Long and the Short of Them

Lindblad’s National Geographic Endeavour will spend the entire day at Isla Isabela, largest island in the Galapagos Archipelago. Less than a decade ago, this island was overrun with feral goats and pigs that settlers brought. The animals’ destroyed the endemic flora and fauna, threatening the survival of land iguanas and giant tortoises. The situation promptied the National Park Service to undertake the world’s largest ever ecosystem restoration mission in a protected area.

On northern Isabela, the goat population numbered 100,000 animals when the eradication project began in 1997. It was a costly, high-tech endeavor that used helicopters for aerial hunting. GIS tracking used radio collars attached to sterilized goats to pinpoint any hidden herds of feral goats. The project, a complete success, endied in 2005. Land iguanas and giant tortoises on Isla Isabela are no longer threatened with extinction.

Our day begins at Urbina Bay (also known as Urvina Bay) on the western shore of Isla Isabela. This is a famous location where in 1954 almost one square mile (1.5 km) of sea bottom including a section of coral reef was instantly lifted 15 feet (5 m) above water by a geological uplift. Records indicate that sharks, lobsters and fish were left on land–some even found in the trees–by local fishermen who noticed the strong stench coming from the area. Uplifts occur in the Galapagos frequently, but this is one of the most dramatic ever witnessed.

Urbina Bay’s Two Hiking Trails

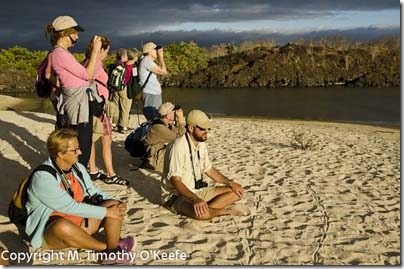

Two hiking trails lead from Urbina Bay. Linda and Tim split up to provide the descriptions of both walks.

Linda’s Hike: Almost 60 years later, the ocean bottom has blended with the landscape and everything looks normal. Yet I can’t help but wonder if another sudden uplifting could be on the calendar for today.

I quickly remove the thought. I’m excited about the chance to see huge tortoises in the wild, our first chance for such an encounter. The Endeavour is offering two morning hikes. The longer one is almost 2 miles (3 km) and goes along the beach passing large boulders and upraised corals before turning inland. A shorter, half-mile version covers only the inland portion.

Short vs Long Trail

I choose the shorter walk because climbing doesn’t over boulders doesn’t seem like the thing. I have a touch of motion sickness and it’s not because the Endeavour rocks and rolls that much. I have an inner ear problem that makes me especially susceptible to the motion of a rough Zodiac ride. The high waves yesterday were too much like a roller-coaster ride. I’m still recovering..

The long hikers leave at 8 a.m. and we follow at 8:30. As the departure times grow closer, I become hesitant about doing the short walk. I don’t want to miss any great photo opportunity but the guides have assured me we will see the same wildlife.

Dolphins escort our Zodiac to shore.

Dolphins escort our Zodiac to shore.

The Zodiac trip to Urbina had an awesome surprise. A group of bottlenose dolphins escorted us from the ship to our wet landing site on the beach. Because our hike is short, naturalist Walter has the Zodiac driver follow the dolphins for 15 or 20 minutes.

Galapagos Hawks Easy Photo Subjects

Once on the beach, we are greeted by five juvenile Galapagos hawks. One hawk tries to tear open a bright yellow mesh dive bag that a hiker left on the beach. What a terrific photo opportunity! I am thrilled with my decision to take the short hike decision so far.

Ambitious Galapagos hawk trying to figure out how to fly off with gear bag.

Ambitious Galapagos hawk trying to figure out how to fly off with gear bag.

As we depart the beach, we split into different groups (a maximum of 16 persons in a group). My naturalist today is Jeffo who was our guide yesterday on Fernandina Island. The first thing Jeffo shows us is a species of cotton called Darwin’s cotton.

Although it is an endemic species, it seems strange to find something so common and ordinary in the Galapagos. This cotton is closely related to the cotton found on the American continent. So scientists believe a cotton seed was blown here by the wind, washed in by the sea or dropped by a bird.

Darwin cotton bears a yellow flower.

Darwin cotton bears a yellow flower.

Animals Hide from the Sun

Jeffo slows down to point out several large iguanas hiding under the trees. It’s a clear day and everything seems to be hiding from the sun. We do spot two giant tortoises: a young one hiding in a hole with only part of its shell visible and a fully grown one sandwiched under thick tree limbs as it tries to keep cool.

Urbina Bay on Isabela Island has some of the Galapagos’ largest land iguanas.

Urbina Bay on Isabela Island has some of the Galapagos’ largest land iguanas.

When we arrive back at the beach, the hawks are still patrolling and taking their photo is easier than taking candy from a baby. Several people in our group brave swimming in the cold water as sea lions watch them from the rocks. I decide to just sit on the beach and watch a couple of eagle rays glide through the water. I also spot sea turtles bobbing their heads above the water for a quick gulp of air. Only in the Galapagos can I have this kind of experience. It’s extremely pleasant.

The best part of this morning’s walk: we were never rushed; unlike some other hikes. I wonder how Tim is doing photo-wise on the longer walk.

The Long, Long, Long Beach Walk

Tim’s Hike: You would think the first groups ashore for the long walk would see more critters than those who come later. Not necessarily so. Our Zodiac is the first to encounter the bottlenose dolphin and they are close, just yards away from us. They are having fun, porpoising first on one side and then the other. No one is sitting in the bow, which would allow photographing them from both sides, so I claim it and begin firing away.

Because we’re on a schedule–our panga drivers need to go back to get the late-comers–we don’t spend much time with the dolphin but go directly to the black sand beach where a Galapagos hawk is sitting high in a tree watching us. The bird seems as curious about us as we are about it. I am able to move as close as I need for my telephoto lens. Any closer and tree branches would be in the way, with the hawk perched right above me.

In addition to its length, having to climb lava rocks on the beach deterred

many from this longer hike.

I’m so intent on taking hawk pictures I didn’t realize how long we’ve been on the beach. I’m the only one taking hawk photos so why a delay? Hikers for the short walk are arriving. It’s 8:30 a.m. before we start our walk.

Can We Please Get Moving?

I notice there is another group walking the beach far, far ahead of us. I soon understand how this happened. Our naturalist leader is an excellent naturalist but perhaps too obsessed about telling us everything we see; some of which we have seen before.

The steep beach slope at Urbina Bay.

We do see many interesting things on the walk, particularly the steep slope created when the shoreline was pushed a half-mile farther out when the sea bottom uplifted. We also find a remarkably colored male iguana starting to glow with his mating colors.

However, we are just leaving the beach when we start encountering short hikers who have spent almost two hours exploring and photographing the inland area where most of the animals are said to be located. It’s now 10:15 and we’re supposed to be back on board at 11:15. Some of us want to pick up the pace to take the inland trail.

A Beached Coral Reef

We find a cluster of boulder-sized coral heads located several hundred yards from the coastline. Corals generally grow only about an inch a year. Some of the coral boulders are shoulder to chin high or even go over our heads. These are monuments to decades, if not centuries, of coral reef development. All of that work was abruptly ended by the uplift. We are just as susceptible to our planet’s quirks. No use in worrying about it.

Some of the coral heads moved inland by 1954’s uplift of the sea bottom.

I would like to spend more time at this location but the remainder of the trail beckons, which several of us continue to pioneer for our group. The pathway here is more overgrown than any other we’ve ever traveled, an indication of how infrequently it is used.

The overgrown trail at Urbina Cove; a trail marker—the last goat on Isabela Island?

Big Land Iguanas in the Shade

Some of the Galapagos’ largest land iguanas are supposed to live here and we find many of them resting under tree braches as well as the burrows where they retreat to from the sun. We also encounter a large tortoise that has pushed itself well back into a dense thicket to escape the sun. The only photo angle available was turtle butt.

Galapagos tortoise seeks seclusion from sun.

Galapagos tortoise seeks seclusion from sun.

The inland path ends at our landing point. Not surprisingly, the other groups left well ahead of us. We finally reboard the Endeavour a half-hour behind schedule.

As we do, a story is circulating about the efficiency of our life jackets. The waves were strong at the landing site and one Zodiac became partially flooded. Contact with the water caused all the life jackets resting on the bottom to inflate. That’s a sight I’m sorry I missed.

Choose Your Naturalist Wisely

The moral of today’s hike: the naturalist guides can both enhance and hinder your shore excursions. Until today all the naturalists have been excellent. It’s surprising to find one so out of step with the rest.

But that’s easily remedied: I’ll pay more attention to which guide is in charge of a particular Zodiac. And act accordingly.

I certainly saw more than Linda did on her short walk. But she enjoyed hers more.

Lindblad Endeavour Galapagos Cruise Links

The Galapagos Experience Endeavour Dining

Galapagos Adventure Upcoming Sustainable Dining Policy

How Darwin Saved The Galapagos Saturday Dining Menus

Galapagos Photo Tips Sunday Dining Menus

What To Pack For Cruise Monday Dining Menus

Getting to Guayaquil Tuesday Dining Menus

Las Bachas Shore Landing Wednesday Dining Menus

North Seymour Shore Landing Thursday Dining Menus

Fernandina & Isabela Islands Friday Finale Menus

Urbina Bay Shore Landing Endeavour Recipes

Life Aboard The Endeavour

More About Life On Board

Puerto Egas Shore Landing

Endeavour’s Floating SPA

Meeting One of World’s Rarest Animals

Puerto Ayoro Walking Tour

Santa Cruz Highlands Tour

Hunting Tortoises in the Santa Cruz Highlands

San Cristobal, Endeavour’s final stop

Follow

Follow

Fill flash would remove the shadowing from this Galapagos hawk’s eye

Fill flash would remove the shadowing from this Galapagos hawk’s eye