Puerto Egas, where wildlife offers a warm welcome

Everyone who takes a Galapagos cruise usually has a favorite shore landing. Mine comes unexpectedly almost midway through the trip when Lindblad’s National Geographic Endeavour takes us to Puerto Egas on Isla Santiago (also known as James Island and Isla San Salvador).

During our afternoon stop there, everything comes together: the sunlight is gorgeous, we encounter a good variety of birds and mammals and also witness lots of lively animal interaction, including a large bellowing male Galapagos fur seal. Best of all, this is one of the most leisurely walks, without the usual and constant push to keep moving.

Ironically, when the Endeavour arrives and anchors off Isla Santiago, there is no hint this will be a special afternoon. Instead, once our Zodiac lands on a narrow rocky beach, the scenery is almost depressing. A dilapidated house sits on a small cliff above us. After we exit the beach for a better view of the old deserted homestead and its empty, fenced fields, the spot seems even more dismal.

Man’s intrusion leaves an unwanted mark

There may be 30,000 people living in the Galapagos, but this is the first evidence of human occupation we’ve seen since sailing from Baltra on Saturday morning. This unexpected detritus of human intrusion is an irritating reminder of past efforts to harvest salt here. Attempts were made between 1928 and 1930, then again later in 1964.

Both attempts caused significant environmental damage. Settlers burned native and endemic trees for firewood and introduced new plants and animals. The Puerto Egas name refers to the last salt company operation, run by Hector Egas. His venture failed when the price of salt in South America dropped so low that operating in the Galapagos became impractical.

Jarring reminders of the humans who once lived here

Darwin’s Toilet

We quickly leave the settlement area and make the short walk across the island’s narrow point to the other side, which is surprisingly different. It’s long black lava coastline that seems to extend endlessly along James Bay, where Charles Darwin’s ship anchored and he explored the interior of Santiago Island. The shore, comprised of an old lava flow that poured into the ocean, has many large inlets and tidal pools created by the erosive force of the rough wave action.

One of these inlets, a vertical chute where the water rises and ebbs as waves regularly crash against the rock, carries the appropriate if undignified name of “Darwin’s toilet.”

In search of fur seals

This lava shoreline is a favorite haunt of fur seals, the smallest of the pinnipeds and creatures we really haven’t encountered closely before. Endemic to the Galápagos Islands, an estimated 40,000 fur seals are spread throughout the islands, apparently much smaller than just a few decades ago. Scientists say the fur seal population was reduced significantly in the 1980s due to the effects of El Nino, which also reduced the local fish populations.

The best known place to see fur seals is Gruta de las Focas, which has a natural bridge above the inlets where fur seals are normally found. They’re present today because, thankfully for us, Galápagos fur seals are the most land-based of all the fur seals, spending at least 30% of their time out of the water. Fortunately, they also do most of their fishing at night since they prefer to spend as many days as possible warming themselves on the lava rocks and only occasionally sunbathing on sandy beaches.

American oyster catchers were common place at Puerto Egas

American oyster catchers were common place at Puerto Egas

Climate changes

Hopefully, the fur seals will be as prevalent here and throughout the Galapagos in coming years since the current climate change seems to have prompted an ambitious group of Galapagos fur seals to look for better fishing waters in Peru. No one is sure why, perhaps because there are more fish there. This migration happened in 2010 when a group of Galapagos fur seals traveled 900 miles (1,500 km) to the northern waters of Peru and established a colony there. It was the first recorded instance of Galapagos seals migrating from their homeland.

Rising water temperatures have been credited as the motivation but the water still averages warmer in the Galapagos. Water temperatures off northern Peru have increased from 62F (17C) to 73F (23C) in the past 10 years; Galapagos water temps average 77F (25C). It’s speculated more such colonies might be established in northern Peru. Still think it’s due to better fish populations in Peru and not the water temperature although the two are often. connected.

Darwin paid scant attention to the fur seals during his visit, perhaps because fur hunters had almost hunted the animals to extinction. On this day fur seals are prominent at Puerto Egas, along with Sally Lightfoot crabs, marine iguanas, American oyster catchers, a Galapagos hawk and more. Two fur seals are in a contest with a sea lion to dislodge the sea lion from its flat rock perch just above the waves.

The sea lion ignores the fur seals’ loud noises and aggressive threats, holding its head high with an expression we interpret to mean something like “Well, there goes the neighborhood!”

Lava gull stalking the Puerto Egas tidal pools

Lava gull stalking the Puerto Egas tidal pools

The matter is semi-resolved when one of the fur seals jumps on an adjoining rock and gradually nudges its way into sharing part of the platform. The sea lion refuses to retreat and both animals end up sharing the space. The second fur seal stays in the water, preferring to swim around and keep out of the way. Once the action subsides, we wander away, careful not to trip over or step on the marine iguanas littering the craggy lava surface like washed-up seaweed.

Tidal pools harbor abundant birdlife

As we walk the shoreline in the direction of the ship, it’s obvious the Puerto Egas tidal pools are attracting the largest variety of birds we’ve ever seen in one location. Even several Darwin finches land in the trees bordering the shoreline only a few yards behind the beach. I lag behind the others for the unusually prime photo ops. It’s what photographers call the “golden” or “magic” hour, very close to sunset. The colors are amazing. This one afternoon almost makes up for the cloudy days on most of the trip.

When I finish photographing the birds in the tidal pools, I catch up with my group and see they are watching a Galapagos hawk dine on a sizable marine iguana. We are perhaps 20 yards from the hawk, which is well aware of our presence but continues to feed while keeping an obvious watch on us.

Close animal encounters

We’ve seen numerous marine iguanas along the coast, more than in most places, and it’s not surprising there would be a natural death the hawk would take advantage of. The hawk carefully watches on us as we photograph/view it.

Galapagos hawk feeds on its prize meal. Fur seal pup.

The day’s highpoint comes near the end of our walk where we encounter a huge male fur seal and his harem. The males are supposed to grow no larger than 5 feet (1.5m) in length and weigh no more than about 145 pounds. This fellow not only looks much larger and scarily impressive because he sits on a rock plateau just a few feet above us.

Seen in profile, this huge male should emphasize why the Galapagos fur seal’s scientific name is Arctocephalus galapagoensis, from Greek words meaning “bear headed.” It doesn’t. The fur seal does have a short, pointed muzzle, along with a small, button nose and large eyes. The muzzle of most bears I’ve seen are considerably longer and the noses larger than button-size.

Think hound dog, instead. However, when the male fur seal starts bellowing at one of his concubines, he draws his lips back and flashes sharp, triangular teeth that make me think of something as deadly as a bear.

Male fur sea offering us some advice: “Stay away!”

Male fur sea offering us some advice: “Stay away!”

Fur seal mating psychology

Dominant male fur seals are enormously protective of their breeding territory, often required to challenge and chase away challengers. This fellow also obviously expends a lot of effort trying to keep his women in line, though he doesn’t seem to have much success. He seems to be loudly coaxing, or whatever—with hands, he might act like a gorilla beating its chest–to impress the only female sharing the platform. She acknowledges his “whatever,” occasionally swaying her head like a boxer in the ring, but eventually just turns and descends to join the other girls below.

Our guide (a woman) explains, “She’s out to prove she wants more than a one-night stand. He needs to step up his game and romance her.”

It seems absurd that a creature this size and fearsome could ever court (date?) a mate. But males of may species do it. Whales and male sharks do it. Magnificent frigate birds do it (remember the males’ big red sacs?). Male blue-Footed Bobbies do it (by building impressive nests and their dancing). Human males do it, too. Instead of impressive nest building, we offer dinner, a show or a concert. We’ve evolved to not interacting in person with a potential mate and sending text messages instead.

In the Galapagos, you realize a lot about life and love.

Lindblad’s National Geographic Endeavour off Puerto Egas

Lindblad’s National Geographic Endeavour off Puerto Egas

Like this:

Like Loading...

Cruising through the Stockholm archipelago

Cruising through the Stockholm archipelago Oceania Marina Concierge Lounge

Oceania Marina Concierge Lounge

Follow

Follow

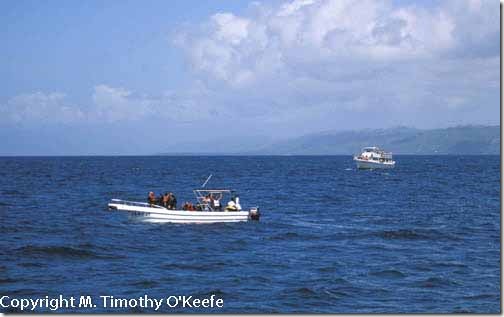

You can choose between large and small whale watching boats.

You can choose between large and small whale watching boats.